Was Gertrude Stein a feminist? Was she homophobic? A naïve racist (à la Gone with the Wind)? A Hitler fan?

Was Gertrude Stein a feminist? Was she homophobic? A naïve racist (à la Gone with the Wind)? A Hitler fan?

These are some of the fascinating questions the upcoming exhibitions in San Francisco will have to address. They are part of the national and international attention focused anew on our literary maverick. Here is some of the quizzical evidence that begs to be addressed, if not worked out.

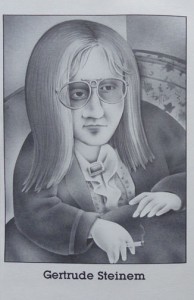

The marvelous double portrait of Gloria Steinem and Gertrude Stein by cartoonist Tom Hachtman will be part of “Seeing Gertrude Stein: Five Stories” at the Contemporary Jewish Museum from May 12 (and later at the National Portrait Gallery in DC). For Hachtman (who gave me the generous permission to use several of his caricatures of Gertrude and Alice) a few lines without words comically declare Stein a feminist – two revolutionaries in one. Stein never declared herself a feminist, but then she wasn’t a party-liner. The only party she ever belonged to was a party of one: Gertrude Stein.

Parties end up limiting and fencing you in. Without membership, you could go almost unnoticed writing one of the most radical early feminist poems I know and which I have often quoted from, here and elsewhere: “Patriarchal Poetry”.

Was Gertrude Stein homophobic? She hid the story of her own first lesbian love affair, Q.E.D., from the world and tried, unsuccessfully, to hide it even from Alice. In another early story, “Melanctha” (in Three Lives), Stein made the same love conflict kosher and publishable by changing the gender of one participant into a man. But the transgressive quality of this autobiographical material escaped nonetheless onto the page by virtue of Stein’s making the lovers black and using language that would have gone unnoticed at the beginning of the century, in a color-blind world. Today it raises interesting questions about Stein’s conscious or unconscious use of racist notions.

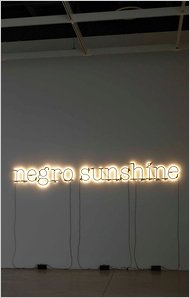

The New York Times reported on Feb. 24, 2011: “A STARTLING sight will soon be hanging in midair in the Madison Avenue window of the Whitney Museum of American Art, just a few blocks from Ralph Lauren, Prada and Gucci: a 22-foot-long neon sign spelling out the words “negro sunshine.”

The New York Times reported on Feb. 24, 2011: “A STARTLING sight will soon be hanging in midair in the Madison Avenue window of the Whitney Museum of American Art, just a few blocks from Ralph Lauren, Prada and Gucci: a 22-foot-long neon sign spelling out the words “negro sunshine.”

It’s the work of the New York Conceptual artist Glenn Ligon, whose midcareer retrospective, “Glenn Ligon: America,” opens at the Whitney on March 10. Taken from “Melanctha,” a 1909 novella by Gertrude Stein about a mixed-race woman, “negro sunshine” is the kind of ambiguous phrase that Mr. Ligon, who is black, uses to speak of the history of African-Americans. ‘I find her language fascinating,’ he said of Stein. ‘It’s a phrase that stuck in my head.’

The artist’s fascination with words evoking race, gayness and other themes of “outsiderness” seems linked to Stein’s own by “raising a controversial or mysterious question and leaving the viewer to work for the answers.“

Another case is point is Stein’s famous remark about Hitler and the Peace Nobel Prize. In 1934, New York Times Magazine reporter Lansing Warren went to interview the bestseller author in Paris for an article titled, “Gertrude Stein Views Life and Politics”. “’I say that Hitler ought to have the peace prize,’ she says, ‘because he is removing all elements of contest and struggle from Germany. By driving out the Jews and the democratic and Left elements, he is driving out everything that conduces to activity. That means peace.’”

One always has to work for answers when reading Gertrude Stein. But in this case, the interviewer left us a clue: “When she laughs, as she often does at the mental confusion produced in her auditor by many of her remarks, her face and body become mobile, and there is something impish in her expression.”