“Not everything can be about everything”– Stein, the worms and the butterflies.

In his last and final book, The Memory Chalet, brilliant historian Toni Judt reminisces about teaching students at the time when feminism, gender and sexual harrassment were discovered.

“When discussing sexually explicit literature—Milan Kundera, to take an obvious case—with European students, I have always found them comfortable debating the topic. Conversely, young Americans of both sexes—usually so forthcoming—fall nervously silent: reluctant to engage the subject lest they transgress boundaries. Yet sex—or, to adopt the term of art, ‘gender’—is the first thing that comes to mind when they try to explain the behavior of adults in the real world.

“Here as in so many other arenas, we have taken the ‘60s altogether too seriously. Sexuality (or gender) is just as distorting when we fixate upon it as when we deny it. Substituting gender (or ‘race’ or ‘ethnicity’ or ‘me’) for social class or income category could only have occurred to people for whom politics was a recreational avocation, a projection of self onto the world at large.

“Why should everything be about ‘me’? Are my fixations of significance to the Republic? Do my particular needs by definition speak to broader concerns? What on earth does it mean to say that ‘the personal is political’? If everything is ‘political,’ then nothing is. I am reminded of Gertrude Stein’s Oxford lecture on contemporary literature. ‘What about the woman question?’ someone asked. Stein’s reply should be emblazoned on every college notice board from Boston to Berkeley: ‘Not everything can be about everything.’”

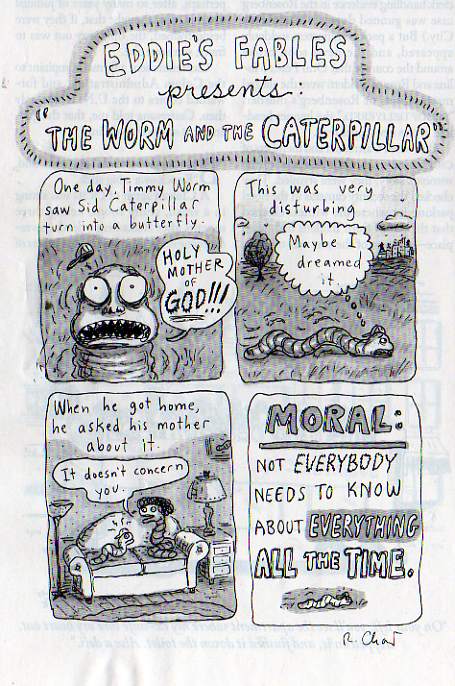

Stein is on everyone’s mind this year, the year of her renaissance. Looking at last week’s New Yorker, I could add she is even on the mind of worms. At least she is, according to my favorite cartoonist, Roz Chast: